Jewish genealogy in Moldova is a story not only about documents, but also about shifting borders, languages and regimes. One and the same person could be born in the Russian Empire, marry in Romania, live through the war under Romanian administration in the Transnistria zone and die in the USSR, without ever leaving their hometown. Bessarabia belonged to the Pale of Settlement; Jews from other regions of the empire actively moved here, and by the early 20th century a dense network of Jewish towns and communities had emerged.

After the First World War the region became part of Romania; in 1940 it was annexed by the USSR, then went through the catastrophe of the Holocaust and deportations to the Romanian-controlled zone of Transnistria. After 1944 came the long Soviet period with its new-style passports, the Russification of names and the mass emigration of Jews at the end of the 20th century. For a genealogist this means that the story of one family can literally be spread across the archives of several countries, and that one and the same person will appear in documents under different states and with different versions of their name and surname.

Historical Context: Bessarabia, Romania, the USSR

To judge realistically what can be found, it helps to keep a simple timeline in mind. In the 19th and early 20th centuries the Jews of Moldova lived in the Bessarabian Governorate of the Russian Empire, within the Pale of Settlement. There were typical shtetls with synagogues, crafts, small trade and active communal life. The main centre was Chișinău, where Jews made up a significant proportion of the population.

In 1918 Bessarabia was united with Romania, which changed the language of administration, the rules of citizenship, the army and the school system, but Jewish life in towns and shtetls continued. In 1940 the region was annexed by the USSR, and in 1941–1944 a large part of the Jewish population was murdered or deported by Romanian and German authorities to camps and ghettos in Transnistria. After the war those who survived either returned to Soviet Moldova or moved on to large Soviet cities, and later to Israel, the USA, Canada and Europe.

Languages, Names and Documents: Why Everything “Moves Around”

Moldovan Jewish genealogy is marked by a constant change of languages and administrative logic. Documents may be written in Russian (sometimes in pre-reform spelling), in Romanian—using either Latin or Cyrillic script—and on tombstones and in communal records one often encounters Hebrew or Yiddish. Another important layer is Soviet passports and forms, where names were re-recorded in modern Russian, sometimes in a very altered form.

In such a setting names and surnames are rarely straightforward. A man called Chaim can easily become Grigori or Grigoriu; Leib turns into Lev; and one and the same surname may appear in three or four spellings in different documents and languages. This is not “an archival mistake” but the normal reality of a multilingual region. That is why, when researching, it is crucial to be mentally prepared for variations and not discard “similar but not identical” versions too quickly.

Place names are another challenge. The same town or shtetl might have a Russian, Romanian or Ukrainian form, while in family stories its name may be slightly distorted. As a result, the place of birth written in a Soviet passport may look and sound different from what you see on old maps, on a matzevah, or in a pre-revolutionary census.

Sources: From Vital Records to Necropolises

The foundation of almost any research is civil status records: births, marriages and deaths. For Jewish Moldova these may be pre-revolutionary communal metrical books, Romanian civil registers of the interwar period and Soviet registry-office records. Some of these documents are kept in the National Archive of Moldova and regional archives; others are held in Romanian and Ukrainian archives, depending on the particular locality and period.

Alongside vital records one can find censuses and revision lists, tax registers, military conscription lists, court and notarial records, school registers, party and Komsomol files. A crucial layer for Jewish genealogy is cemeteries: tombstone inscriptions in Hebrew or Yiddish often contain the Hebrew given name, the father’s name, a note about social status, and sometimes the place of origin. All this helps link Soviet and Romanian documents to the earlier religious tradition.

Archives and Online Resources for Moldova and Bessarabia

Today a researcher usually combines two key approaches: classical archival work and online search. The archives of Moldova, Romania and Ukraine hold original registers, censuses, court files and many other records. To understand what kinds of documents exist for a particular shtetl, it is helpful to use specialised guides and surveys. One of the most important is the work of Miriam Weiner “Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova” and the accompanying Routes to Roots Foundation project, which describe for each town and district what Jewish and general records survive and in which archives they are stored.

In parallel, online databases have been developed for many years. First of all, these are the JewishGen databases for Romania and Moldova, which contain hundreds of thousands of entries on births, marriages, deaths, censuses and other sources for Bessarabia, including Chișinău and other towns. FamilySearch and dedicated wiki pages help you see which collections have been digitised and which are available only on-site. Another important group of sources consists of cemetery projects that document tombstones in modern Moldova and neighbouring regions.

A key resource is also Holocaust databases, especially Yad Vashem’s Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names and the Pages of Testimony. They often include the place of birth, parents’ names, marriage details, pre-war address and information about relatives who survived. For Jewish families from Bessarabia these records are sometimes the only source of information about branches destroyed in 1941–1944.

Where to Start: Home Archives and the “Skeleton” of the Tree

In practice the journey almost never begins in an archive; it starts in your own family. Record what older relatives remember, carefully collect all birth and marriage certificates, military IDs, passports, diplomas, and old photographs with captions. From these materials you need to extract all variants of names and surnames, approximate years and places of key events, and migration or evacuation routes.

These first notes are the “skeleton” of your future tree. They keep you from getting lost in online databases full of namesakes and help you distinguish “your” Chaim Rosenberg from someone completely unrelated. At this stage it is also useful to draw a simple family scheme for at least two or three generations: who is related to whom, where they lived and what they went through. Even if there are many gaps in the documents, this is enough to move forward and send more targeted requests.

Archival Requests and Online Search: How to Combine Them

The next step is parallel work with archives and online platforms. For Soviet-era events you send requests to registry offices and archives in the locality where the birth, marriage or death occurred. For earlier records from Bessarabia and Transnistria you may have to contact Romanian or Ukrainian archives, taking into account the historical jurisdiction of the territory at the time. When writing a request it is important to provide as much information as you have: all known surname variants, an approximate year, religion, and the presumed locality.

At the same time you can work through JewishGen, FamilySearch and other databases. A good practice is to search not only for the “ideal” spelling of the surname, but for all reasonable variants, and also for combinations of given name plus town. Variants of transcription, spelling mistakes and quirks of old alphabets are not obstacles here but the norm you need to be ready for.

Holocaust, Deportations and Repressions: A Special Layer of Research

For many Moldovan Jewish families the story includes traumatic episodes: the Holocaust, deportations and post-war repressions. Information on people killed or missing in 1941–1944 can be found in Yad Vashem databases, in Soviet investigative files and the records of commissions that documented occupation crimes, as well as in specialised studies on Transnistria. There you can encounter lists of deportees from Bessarabia, details about ghettos and camps, transport routes and places of mass murder.

Working with such materials calls for special tact. The facts you uncover can be very painful for older relatives. It can be wise to discuss in advance how and to whom you will pass on disturbing details, and to think about whether all of them should be included in public materials such as a family book or website.

Diaspora and DNA Genealogy

Almost every Moldovan Jewish family tree has branches far beyond the borders of present-day Moldova. After the war and especially in the second half of the 20th century, relatives moved to Israel, the USA, Canada, Germany, France and other countries. At a certain point, Moldovan and Romanian records are supplemented by passenger lists, naturalisation files, displaced persons camp forms, Israeli and Western archives.

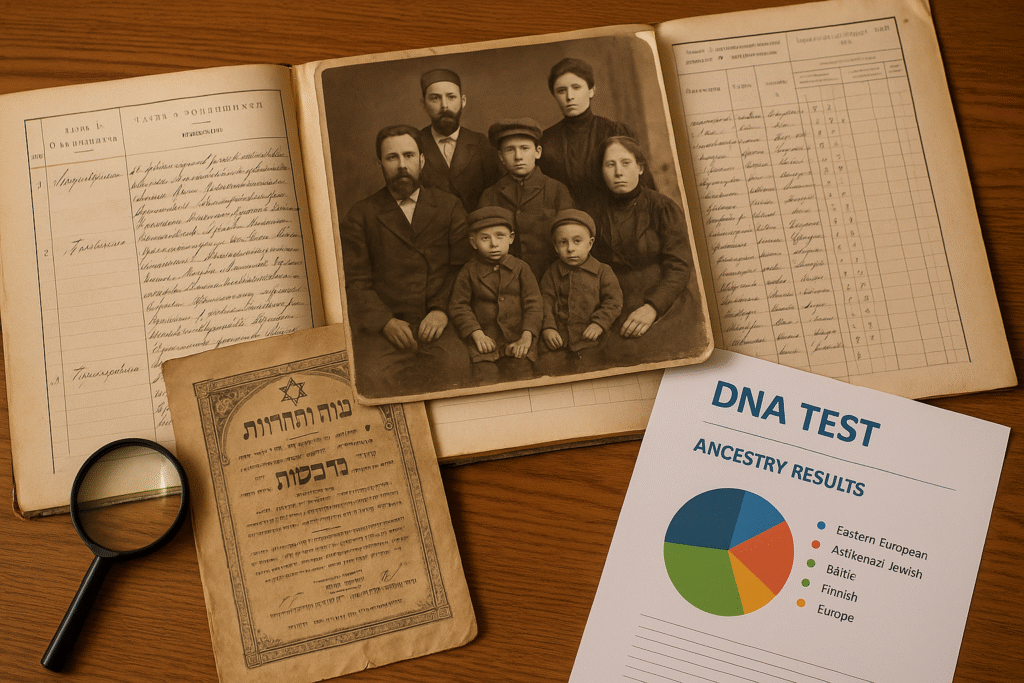

In recent years genetic testing has also become part of the toolbox. For descendants of Bessarabian Jews, DNA tests can help confirm or refute assumed relationships with namesakes in other countries, identify distant cousins and reconstruct branches for which almost no documents survive. It is important to remember that genetics does not replace classical genealogy but works alongside it: without a documentary “skeleton”, any DNA matches remain only hypotheses.

When It Makes Sense to Turn to a Professional

The time to involve a professional researcher usually comes when you hit a “glass ceiling”. Archive replies say “no records found”, the surname is too common, the geography is confusing, and there is simply no time for systematic work. A specialist in the region knows the structure of local archives, the specifics of their collections and typical traps, and is familiar with the necessary languages, scripts and abbreviations.

The result of professional research can be not only a family tree, but also a detailed narrative: with copies of documents, photographs of towns and shtetls, descriptions of migrations and historical context. Such a report often becomes the basis for a family book or album to be passed down to future generations.

How to Preserve the Results and What to Do Next

Finishing the research always raises the question of how to preserve what you have found. Some people compile a family book or album with documents, commentary and photos; others prefer digital trees on specialised platforms, a family website or a private social-media group for relatives. A natural next step is travelling to ancestral places—Chișinău, Bălți, Soroca and smaller shtetls—where you can still see matzevot on old Jewish cemeteries and catch a glimpse of the old shtetl atmosphere.

If you reduce everything to one simple step, it will be a very modest one: start small. Record the stories of the elders, sort out the “drawer full of papers”, and sketch the first two or three generations of your family tree. This alone is enough to move on to archives, databases and professional help. Jewish genealogy in Moldova is complex and multi-layered, but precisely for that reason it gives a powerful sense of connection—with your family, with the history of the region and with those who lived there before us.

If you would like not only to reconstruct your family’s documentary history but also to complement it with genetic research—DNA tests to search for and confirm family links—you are welcome to work with us. Go to the “Contacts” section on our website and get in touch: we will advise you on which genetic tests make sense in your particular case and how best to combine DNA results with classical genealogical research.